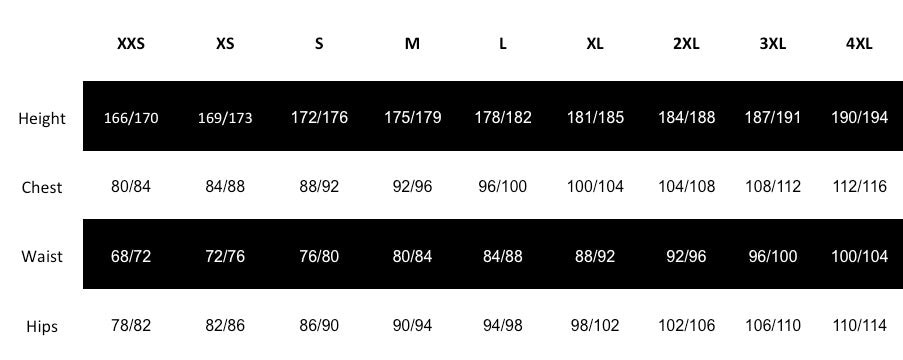

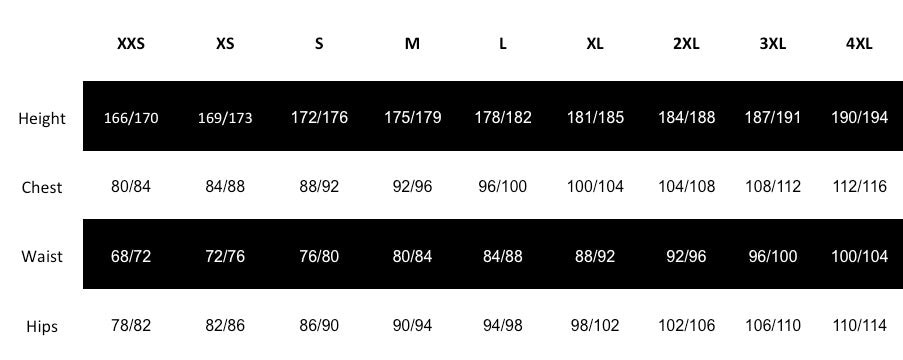

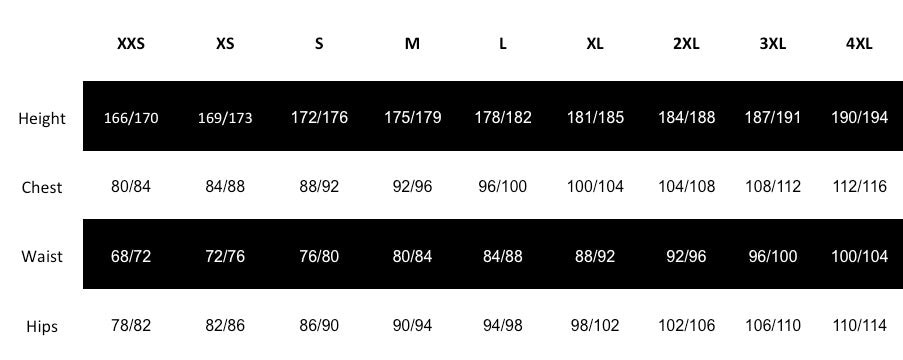

Size Chart

Men's

Women's Bib Shorts & Jerseys & Vests

Women's Jackets

Arm Warmers

First held in 1876, Milano Torino is the oldest of the Italian Classic races and is especially significant to Italian cycling, global cycling, and to our entire team at Marcello Bergamo.

The 199 km route begins in the outskirts of Milano (Milan) and finishes in the Fausto Coppi velodrome on the Eastern outskirts of Torino (Turin). It covers slightly undulating terrain that includes the intimidating the Superga Climb, then finishes with an exciting descent to the finish line.

Historically, Milano Torino was held a week prior to Milan-San-Remo, allowing the world’s biggest cyclists to test themselves before the event. Anyone who won Milano Torino was immediately seen as the favourite for Milan-San-Remo.

Heading into the 1973 race, Eddy Merckx had dominated the early Spring Classics, and Belgian riders had won the previous two editions of the race. Italian fans yearned for a local champion, putting an intense amount of pressure on the Italian contingent. One of these hopefuls was a young Marcello Bergamo.

Marcello lived in the region and often trained on the roads between Milano and Torino. He knew every centimetre of this race and was hungry for the win. The week prior, he tested himself against his training partners, including his brother Emanuele and seasoned professionals Luciano Borgognoni and Adriano Passuello, in order to prepare for the race.

His mind and body were ready, but doubts still lingered about whether it would be enough to overcome some of the world’s top cyclists.

The day of the race arrived and the riders were met with unseasonable rains and freezing temperatures, only made worse by a strong headwind. Their nerves were heightened further with news of a metalworkers strike that would delay the start of the race. The mood was bleak as the riders awaited the start and endured the harsh elements.

Finally, an hour after the scheduled start, the race began. There were several attempts by riders to create a breakaway group, but nothing stuck. Then, 100 km into the race, the pack was disrupted by a small crash and several riders seized the opportunity to attack the leaders.

This led to a split of the peloton, with the strongest riders well out ahead. The group included the likes of Dancelli, De Vlaeminck, Lasa, Bitossi, Merckx, and Marcello. At this point, it was clear this would be the group that went to the line, with the winner likely being decided by the Superga Climb.

Averaging above 10%, with long sections between 13% and 18%, Superga was often where the elite riders made their move and set themselves up for a strong finish. This year was no different.

As soon as they hit the climb Dancelli attacked and after a short while Marcello decided to follow. He caught and passed Dancelli after about 1km, remaining out front throughout most of the climb but with only a 100-metre advantage.

“I felt good, really good, and for some reason I was calm and confident,” Marcello recalls.

By the end of the climb, Marcello was joined by Merckx, Bitossi, De Vlaeminck, Lasa, and a few others, and the riders made their descent off the Superga into the outskirts of Torino.

As the group entered the Velodrome Bitossi sprinted ahead with Lasa and Merckx on his wheel, followed by De Vlaeminck and Marcello. With just 30 metres to go, Bitossi went wide and De Vlaeminck made a move for the lead.

The small group was spread across the width of the track. Marcello was still on Merckx’s wheel and seized his opportunity. With a final explosive effort, Marcello surged out of Merckx’s slipstream and beat everyone to the line.

The crowd went crazy.

It had only been a few years before when Marcello had said in an interview that he wanted to win his hometown race. Now, not only had he won the event, but he had beaten the world’s best one day specialist and the sport’s most prolific winner in a thrilling sprint to the line to do it.